A Cape Cod Tale: "Black" Sam Bellamy & the Whydah

There is a lot of history that slowly passes as the short, dramatic and easy to remember versions take hold. As a result, there is truth everywhere that is fading away. Some is lost to urban sprawl, and some to books no longer read. Some to MTV and short attention spans, other relics are washed away by years of storms, sinking back into the wet sand to rot with time.When we think of pirates we most often think of the images and environs that movies, children’s books and video games have left us. Pirates of the Caribbean: looting and pillaging in far off tropical climes, burying hordes of treasure and carousing off into the vanishing mists of legend. Many of those legends are rooted in fact, but there is more meat to the stories than the icons leave us, and so much truth around the periphery that has been lost.

New England, for example, was once a flourishing region of pirate activity. Privateers and worse sailed from ports like Salem, Boston, Newport, Providence and New York. Rhode Island was reknown for it’s rather loose rules when it came to discouraging the trade. Newport’s own Captain Thomas Tew was one of the more famous pirates of the Madagascar theatre, until his old shipmates convinced to him ship out on the account once more for old time’s sake. He lost his belly to a well placed Arab cannon shot and died on the quarterdeck, bleeding. He is said to have left treasure buried in the Narragansett Bay area, perhaps in Newport, Sakonnet Point, or out on Hope Island, but none has ever been found.

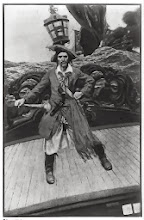

Cape Cod, too, has it’s buccaneering past. How much of it will be lost forever we will never know, but there is still evidence if you know where to look. One colorful tale associated with the cape is that of Captain Samuel Bellamy. Bellamy was born in England and came to Cape Cod in 1715. Here he fell in love with Maria Hallett, a local girl whose attraction may, in fact, have lured him to his death. He left for the Caribbean to excavate for treasure from Spanish Galleons sunk in a hurricane, but his venture was unsuccessful and he ultimately turned pirate. “Black” Sam Bellamy’s crew took over fifty ships in the course of a year. One of his greatest prizes was the capture of the Whydah, a slave ship rich in gold dust, ivory tusks and other treasure from Africa. The Whydah, a three masted galley of three hundred tons burthen, with eighteen cannon and a crew of fifty, became Captain Bellamy’s flagship.

In the spring of 1717 Bellamy’s band of cutthroats came north, past the colonies in Bermuda, Virginia, Maryland and New York. It is not known what brought Bellamy back north from the Caribbean. He is said to have begun work on a fort at the Machias River in Maine, in an attempt to create a place for a free society of Pirates, much as the Isle Sainte Marie off of Madagascar is said to have been. Although the idea is intriguing, those with a more romantic flair lean toward the idea that it was his love for Maria Hallett that brought Bellamy north to his doom on the shores of Cape Cod. On their way to New England, the pirates continued to prey on shipping. One unfortunate but bold Boston sailor, a Captain Beer, had his sloop taken off of Block Island. He related the tale that Bellamy and his crew took all of his goods, then decided they could not risk giving him back his ship. Bellamy’s speech to the captain is chronicled in Captain Charles Johnson’s A General History of the Robberies and Murders of the Most Notorious Pirates, and testifies to the rebellious freedom that drew many to the life of a pirate rogue:

"I am sorry they won't let you have your sloop again, for I scorn to do any one a mischief, when it is not to my advantage; damn the sloop, we must sink her, and she might be of use to you. Though you are a sneaking puppy, and so are all those who will submit to be governed by laws which rich men have made for their own security; for the cowardly whelps have not the courage otherwise to defend what they get by knavery; but damn ye altogether: damn them for a pack of crafty rascals, and you, who serve them, for a parcel of hen-hearted numbskulls. They vilify us, the scoundrels do, when there is only this difference, they rob the poor under the cover of law, forsooth, and we plunder the rich under the protection of our own courage. Had you not better make then one of us, than sneak after these villains for employment?"

When the captain replied that his conscience would not let him break the laws of God and man, the pirate Bellamy continued:

"You are a devilish conscience rascal, I am a free prince, and I have as much authority to make war on the whole world, as he who has a hundred sail of ships at sea, and an army of 100,000 men in the field; and this my conscience me: but there is no arguing with such snivelling puppies, who allow superiors to kick them about deck at pleasure."

During the voyage north Bellamy had secured a small fleet of three ships: the Whydah, a snow under the command of pirate captain Montgomery, and a small merchant pink laden with Madeira wine. Drunk from the capture of a merchant vessel laden with wine, the crew ran into a gale as they tried to pass north from Nantucket Shoals up around the eastern arm of Cape Cod. The northeaster ultimately drove the ships onto the shoals off of the coast of Wellfleet, near what is today Marconi Beach. All save two of the souls on board the Whydah perished in the surf as the ship was broken up by the seas. One, Thomas Davis, had been forced into the crew when his ship was taken earlier that year. Much of what we now know about Bellamy we know through his accounts. The other was a Nauset Indian named John Julian, who had washed up on the beaches of his homeland. That evening, Davis and Julian sought help at the home of local Wellfleet residents, who with their neighbors scavenged up as much of the ocean’s bounty as they could. In the morning, when other local Cape Codders arrived, they found bodies and coins scattered all over the beach.

In the years that have followed many people have found the occasional artifact washed up on the shore. But, it was not until Barry Clifford, a local treasure hunter, discovered the remains of the wreck of the Whydah in 1985 that the true scope of Bellamy’s treasure was known. Clifford’s discoveries continue to this day, and can be viewed at the Expedition Whydah Museum in Provincetown, MA. This is one of only two pirate wrecks ever found in modern times, and the artifacts tell the story of what pirate life was truly like.

So, if you find yourself yearning for the sea and a bit of adventure, take a drive out on route 6 to Marconi Beach in Wellfleet. Perhaps, if a storm has just come through, you’ll find an old coin or some musket shot washed up on the beach. And, if your appetite is only slightly satisfied by the waves of the Atlantic, ceaselessly rolling over the graves of Bellamy and his men, head on north to Provincetown Wharf and the Whydah museum to get a glimpse of real history before it fades…

New England, for example, was once a flourishing region of pirate activity. Privateers and worse sailed from ports like Salem, Boston, Newport, Providence and New York. Rhode Island was reknown for it’s rather loose rules when it came to discouraging the trade. Newport’s own Captain Thomas Tew was one of the more famous pirates of the Madagascar theatre, until his old shipmates convinced to him ship out on the account once more for old time’s sake. He lost his belly to a well placed Arab cannon shot and died on the quarterdeck, bleeding. He is said to have left treasure buried in the Narragansett Bay area, perhaps in Newport, Sakonnet Point, or out on Hope Island, but none has ever been found.

Cape Cod, too, has it’s buccaneering past. How much of it will be lost forever we will never know, but there is still evidence if you know where to look. One colorful tale associated with the cape is that of Captain Samuel Bellamy. Bellamy was born in England and came to Cape Cod in 1715. Here he fell in love with Maria Hallett, a local girl whose attraction may, in fact, have lured him to his death. He left for the Caribbean to excavate for treasure from Spanish Galleons sunk in a hurricane, but his venture was unsuccessful and he ultimately turned pirate. “Black” Sam Bellamy’s crew took over fifty ships in the course of a year. One of his greatest prizes was the capture of the Whydah, a slave ship rich in gold dust, ivory tusks and other treasure from Africa. The Whydah, a three masted galley of three hundred tons burthen, with eighteen cannon and a crew of fifty, became Captain Bellamy’s flagship.

In the spring of 1717 Bellamy’s band of cutthroats came north, past the colonies in Bermuda, Virginia, Maryland and New York. It is not known what brought Bellamy back north from the Caribbean. He is said to have begun work on a fort at the Machias River in Maine, in an attempt to create a place for a free society of Pirates, much as the Isle Sainte Marie off of Madagascar is said to have been. Although the idea is intriguing, those with a more romantic flair lean toward the idea that it was his love for Maria Hallett that brought Bellamy north to his doom on the shores of Cape Cod. On their way to New England, the pirates continued to prey on shipping. One unfortunate but bold Boston sailor, a Captain Beer, had his sloop taken off of Block Island. He related the tale that Bellamy and his crew took all of his goods, then decided they could not risk giving him back his ship. Bellamy’s speech to the captain is chronicled in Captain Charles Johnson’s A General History of the Robberies and Murders of the Most Notorious Pirates, and testifies to the rebellious freedom that drew many to the life of a pirate rogue:

"I am sorry they won't let you have your sloop again, for I scorn to do any one a mischief, when it is not to my advantage; damn the sloop, we must sink her, and she might be of use to you. Though you are a sneaking puppy, and so are all those who will submit to be governed by laws which rich men have made for their own security; for the cowardly whelps have not the courage otherwise to defend what they get by knavery; but damn ye altogether: damn them for a pack of crafty rascals, and you, who serve them, for a parcel of hen-hearted numbskulls. They vilify us, the scoundrels do, when there is only this difference, they rob the poor under the cover of law, forsooth, and we plunder the rich under the protection of our own courage. Had you not better make then one of us, than sneak after these villains for employment?"

When the captain replied that his conscience would not let him break the laws of God and man, the pirate Bellamy continued:

"You are a devilish conscience rascal, I am a free prince, and I have as much authority to make war on the whole world, as he who has a hundred sail of ships at sea, and an army of 100,000 men in the field; and this my conscience me: but there is no arguing with such snivelling puppies, who allow superiors to kick them about deck at pleasure."

During the voyage north Bellamy had secured a small fleet of three ships: the Whydah, a snow under the command of pirate captain Montgomery, and a small merchant pink laden with Madeira wine. Drunk from the capture of a merchant vessel laden with wine, the crew ran into a gale as they tried to pass north from Nantucket Shoals up around the eastern arm of Cape Cod. The northeaster ultimately drove the ships onto the shoals off of the coast of Wellfleet, near what is today Marconi Beach. All save two of the souls on board the Whydah perished in the surf as the ship was broken up by the seas. One, Thomas Davis, had been forced into the crew when his ship was taken earlier that year. Much of what we now know about Bellamy we know through his accounts. The other was a Nauset Indian named John Julian, who had washed up on the beaches of his homeland. That evening, Davis and Julian sought help at the home of local Wellfleet residents, who with their neighbors scavenged up as much of the ocean’s bounty as they could. In the morning, when other local Cape Codders arrived, they found bodies and coins scattered all over the beach.

In the years that have followed many people have found the occasional artifact washed up on the shore. But, it was not until Barry Clifford, a local treasure hunter, discovered the remains of the wreck of the Whydah in 1985 that the true scope of Bellamy’s treasure was known. Clifford’s discoveries continue to this day, and can be viewed at the Expedition Whydah Museum in Provincetown, MA. This is one of only two pirate wrecks ever found in modern times, and the artifacts tell the story of what pirate life was truly like.

So, if you find yourself yearning for the sea and a bit of adventure, take a drive out on route 6 to Marconi Beach in Wellfleet. Perhaps, if a storm has just come through, you’ll find an old coin or some musket shot washed up on the beach. And, if your appetite is only slightly satisfied by the waves of the Atlantic, ceaselessly rolling over the graves of Bellamy and his men, head on north to Provincetown Wharf and the Whydah museum to get a glimpse of real history before it fades…

4 Comments:

This lesson in fading history points out that some societal tensions are timeless. Could we take Black Sam's diatribe as a call to the road less regulated, if not less traveled? Could that same argument be used to call young men to bike gangs or hippies to communes in Thailand? Indeed, in Philip Caputo's "The Horn of Africa" the mercenaries are trying to commit acts that bring them decidedly outside of the realm of human society. I wonder if it is as much a lifestyle choice as a means of support. Look at many of the other nouveau riche in different times- often they were content to join the establishment once they were accorded the status their wealth afforded.

Perhaps Cornelius Quick could tell us what became of successful pirates who made it to old age. To what extent did the eqalitarian nature of piracy affect the fledgling colonies, and were there colonies that could have been considered more affected (like Rhode Island)?

It is good to see Traveler back in-country and making useful insights, as well!

The lure of the pirate's lifestyle certainly has it's parallels through history. The Wild West and the streets of Compton bear a striking resemblance to the open seas of colonial times. Many of the same patterns of class, economics, culture, counter-culture and violence show themselves in each.

It strikes me that any time there is a vast disparity in the wealth across different levels of society, there is also the presence of societal controls (government, religion, good manners...) to maintain that stratification. During these times two types of characters appear to challenge society's rules. I will refer to them as the gangsta and the rockstar, because I want to, and because I can.

Whenever a borderland appears where the rules are less easily enforced, these two types appear and manage to take advantage of the opportunity, but it is usually a messy affair. The gangsta is looking for a means of easy gain without subscribing to the system. Violence is an option. The rockstar, however, is drawn by a craving for freedom from the rules of society. The fringe lifestyle brings both types the opportunity to obtain what they are looking for, but it often carries enormous risks, as well.

In regards to this post, I would read Bellamy's speech and see him as more of a rockstar, caught up in the ideals of rebellion. Nevertheless, he is probably reliant upon a crew made up of gangstas to carry out the dirty work of piracy on the high seas.

I think Traveler's point is a good one. Moreover, I think an upcoming post will examine several interesting ideas: what happened to the successful pirates? Is there a marked difference between the success of rockstars and gangstas as they try to cross back into society? What other types emerge? And, finally, what effect did piracy have on democracy? Stay tuned...

My sister lives on the Cape. She says they look for treasure from the Whydah all the time. But it gets murky and the sand kicks up...

As a descendant of the Cape Cod Halletts, I was fascinated by the tale of Black Sam Bellamy and Maria Hallett. However, I eventually tired of everyone declaring Maria a witch, so I set out to set the record straight. The result was House Call to the Past, a fun high-spirited time travel. It is available at almost all online bookstores or can be ordered from your local bookstores. I am working on Port Call to the Future, which divulges what happened to Black Sam. Remember, his body was never found!

Janet Elaine Smith, multi-genre author

Post a Comment

<< Home