Pop's Last Post

I was in my grandfather’s hospital room in the late 1970’s

when a doctor came in to go over his medical history. My grandfather, who was

both pleasant and a bit stoic, answered the questions matter-of-factly, but in

a thick Yorkshire brogue which I secretly loved to hear. The initial question

was very basic, but the answer surprised us all.

I was in my grandfather’s hospital room in the late 1970’s

when a doctor came in to go over his medical history. My grandfather, who was

both pleasant and a bit stoic, answered the questions matter-of-factly, but in

a thick Yorkshire brogue which I secretly loved to hear. The initial question

was very basic, but the answer surprised us all.

“When was the last time you saw a doctor?” the young intern

asked.

“1917” was Pop’s reply.

The intern looked to us with raised eyebrows. Clearly he

felt this was a mistake, and that my ninety something patriarch was not of

sound mind. But Pop was still quite sharp, and we indicated that the doctor

should continue to ask him the questions.

“And what were you hospitalized for?”

“My leg”

“What was wrong with your leg at the time?”

“It had a piece of the Kaiser's shrapnel in it”

“And you’ve never been to a hospital since?”

“No.”

That was it, no story, no bragging, no lecturing this youngster

about never needing doctors, no reminiscing about the war. Get on with it.

Of course, as a young boy, the scene stuck out in my mind. I

was determined to find out more about Pop’s wartime experiences. But, with his advanced

age, one hospitalization led to another, and in due time we said goodbye to Pop

and lost him from this world.

Last week, while going through family papers, I came across

Pop’s war diary from the First World War. His words were succinct, as usual,

but here is his story, as best I can relate.

My grandfather, George Herbert Ramsden, was born in the city

of Wath-on-Dearne, in the West Riding of Yorkshire, England, in 1885. He spent

most of his early life in Bingley, where he was indentured in an apprenticeship

to learn the painting trade. His father was a cook, who ran a fish and chip

shop. As a young man, he and his friends would stroll the lanes of Bingley in

the evening,

singing songs to the girls who strolled the same lanes. It was there that he met Rose Ann Oldfield, a collier’s daughter. After courting for some time, he proposed to her one day at Druid’s altar, an old stone formation looking out over the moors. On the day they were married, he was so excited when he saw her appear at the back of the church that he ran to her and walked her down the aisle himself.

singing songs to the girls who strolled the same lanes. It was there that he met Rose Ann Oldfield, a collier’s daughter. After courting for some time, he proposed to her one day at Druid’s altar, an old stone formation looking out over the moors. On the day they were married, he was so excited when he saw her appear at the back of the church that he ran to her and walked her down the aisle himself.

Rose had several

relatives who had emigrated from England to the United States and were living

outside of Boston, Massachusetts. The two decided to join them and look for

opportunity there, so in the early 1900’s they crossed the Atlantic and began a

new life in America. They had a daughter, Irene, in 1911. A few years later, in

1914, fighting broke out in Europe and England joined France and Belgium in

fighting Kaiser Wilhelm and the German Army on the Western Front.

Despite the fact that my grandfather was now 30 years old,

with a young family, successfully settled in a new country, his sense of duty

was calling him back to England. And even though the Germans declared a

submarine blockade around England, sinking every ship they found, George, Rose

& Irene set sail back to their homeland. The journey was uneventful, save for

a friendship that the family (especially 4 year old Irene) developed with the

Captain. When the trip was over the Ramsden family settled back in Yorkshire,

but the Captain and the ship were both lost to the German submarines on their

return trip to America.

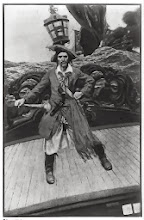

Back in England Pop

enlisted in the Army and became a member of the Black Watch. The Black Watch

were a Scottish regiment, known as “the Ladies from Hell” because they would proudly

wear their kilts into battle. In due time he was trained as a machine gunner

and sent across the channel with his regiment to join the troops in Northern

France. They moved across France and Belgium with full packs, to places like Camiers,

Marquay, Arras, Fampoux, St. Julien, St. Omer, St. Momelin, Poperindge and finally

Ypres. At Ypres the English troops had trouble pronouncing the city’s name

properly, so they took to calling it “Wipers”.

In Ypres Pop was put to work as a runner, possibly because

of his maturity. Runners were charged with hand delivering orders from Brigade

headquarters out to the commanders on the front lines, whose positions could

change daily with no regular means to communicate the changes. This was not

always an easy job, in a country full of mazes of trenches and barbed wire,

pillboxes and shelled out forests. One day he was delivering a message in a new

section of countryside and he became disoriented. The lane he was on forked,

and he was too close to the German front lines to risk going the wrong way. He

paused for a time, in doubt over what to do, but as he rested there a cat

suddenly emerged out of the lonely landscape and, looking back at him, walked

away down one of the paths. Pop chose to follow the cat, and it led him safely

to the allied lines.

In Ypres Pop was put to work as a runner, possibly because

of his maturity. Runners were charged with hand delivering orders from Brigade

headquarters out to the commanders on the front lines, whose positions could

change daily with no regular means to communicate the changes. This was not

always an easy job, in a country full of mazes of trenches and barbed wire,

pillboxes and shelled out forests. One day he was delivering a message in a new

section of countryside and he became disoriented. The lane he was on forked,

and he was too close to the German front lines to risk going the wrong way. He

paused for a time, in doubt over what to do, but as he rested there a cat

suddenly emerged out of the lonely landscape and, looking back at him, walked

away down one of the paths. Pop chose to follow the cat, and it led him safely

to the allied lines.

At night he slept in “the tunnels” as he called them. These

were huge expanses of underground tunnels dug by volunteer Sappers recruited

from the coal mines of Wales and Yorkshire. They housed the English troops deep

underground, out of danger from German artillery, and gave the miners an

additional launching point to tunnel under the German lines and plant

explosives. Even today the farms in that countryside are dotted with craters

that testify to the “clay-kickers” who carried out such destructive and

demoralizing operations against the enemy.

In July of 1917, Pop

was stationed just north of Ypres on the Yser canal bank, just in front of

Pilckem Ridge. He regularly ran messages to the front, while the English Army

began gearing up for a major offensive. Daily artillery activity increased

shelling of the German lines, and the Germans responded with barrages of their

own. On July 2nd his diary relates heavy shelling of their positions

towards morning. During this period, he also acted as a guide, joined work

parties in repairing the trenches, and both wrote and received a number of

letters from home.

On July 31, 1917, Pop awoke and was ordered to Headquarters,

where he was given a message to deliver to Major C.C.L. Barlow of the

Lincolnshire Regiment. His diary tells the story quite clearly:

Stayed in tunnel until 6 a.m. Sent with message to Major Barlow to our

front line. Found him at Hindenburg Farm. Went back to Brig H.Q. Sent back to

Section got nearly there when struck by shrapnel in the knee. Wound dressed in

shell hole again at canal bank. Night at 47 C.C.S.

Stayed in tunnel until 6 a.m. Sent with message to Major Barlow to our

front line. Found him at Hindenburg Farm. Went back to Brig H.Q. Sent back to

Section got nearly there when struck by shrapnel in the knee. Wound dressed in

shell hole again at canal bank. Night at 47 C.C.S.47 C.C.S. was the Casualty Clearing Station. The next day he was moved by train to Camiers, where he was treated in a hospital for a few days and then put on a hospital ship and sent back to England for his recovery at Oxford. The wound probably saved his life, for what he did not know was that July 31, 1917 was the very first day of the Battle of Passchendaele, also known as the 3rd Battle of Ypres.

The engagement lasted more than four months, until early

November. The unimaginable battlefield conditions are legendary. After

English artillery softened the German positions with over one million artillery rounds, record

rainfall hit the region and turned the battlefield into a mass of mud and

flooded shell holes. Men and horses became stuck in the mire and literally

drowned in the mud. Meanwhile, wave after wave of men perished in a futile

effort to gain mere yards of territory. The first wave of English troops to

attack were driven back by the Germans, suffering 70% casualties. By November

when the battle ended, nearly 250,000 English troops had perished on the

battlefield along with approximately 400,000 Germans. Major Barlow, who

received Pop’s message from H.Q. that morning, lived until November but died

just days before the battle was over, though his remains were never able to be

recovered. He is memorialized in a cemetery in Belgium.

To this day the Belgians honor the fallen who came to defend them in a daily ceremony that has been conducted without fail from July of 1928 until this day (with the only exception being during the Second World War, when they were under German occupation, again). The solemn ceremony, called “the Last Post”, is conducted at the Menin Gate in Ypres at dusk each day. Traffic is stopped while a bugle plays the tune that would sound the end of the day to English lines.

To this day the Belgians honor the fallen who came to defend them in a daily ceremony that has been conducted without fail from July of 1928 until this day (with the only exception being during the Second World War, when they were under German occupation, again). The solemn ceremony, called “the Last Post”, is conducted at the Menin Gate in Ypres at dusk each day. Traffic is stopped while a bugle plays the tune that would sound the end of the day to English lines.

Pop was lucky to have made it out of the war alive, and

though his story possesses no standout heroics, learning it helped me to understand

the true sacrifice of his generation, which even now is fading from our

collective memory. This week will mark the 100th anniversary of the

outbreak of the war to end all wars. It also marks the 98th anniversary

of the battle of Passchendaele, and of my grandfather’s 1917 trip to the

hospital. Peace.